** By Micheal Jimoh **

Investigative journalists get their adrenalin pumping faster when they take on very important personalities or lofty institutions as subjects for books in progress. It’s especially so if such investigations concern individuals or institutions with question marks over their private and professional conduct while in public service.

Pulitzer-prize winning American investigative journalist Seymour Hersh would have felt precisely that way in the course of writing what he claimed to be an expose on J F Kennedy before and during his presidency – his serial philandering, his many health problems and father’s close ties to the mafia. There is, also, the Kennedy clan’s proclivity for reckless misadventures and sometimes getting away with it – turning them into some kind of revered and untouchable American family.

When The Dark Side of Camelot was finally published in 1998, critics all over panned it, describing it as fanciful stuff dreamed up by the same author of the more credible My Lai Massacre. Except for a few dissenting voices, most American critics and scholars took The Dark Side for what it was, a sensationalist publication hastily put together by an otherwise brilliant author looking to make oodles of cash with no immediate concern or regard for truth.

British investigative journalist, David Yallop would most certainly have felt that adrenaline rush when he started researching into the circumstances under which Pope John Paul 1 died after only 33 days as Pontiff. A Vatican insider had sent a discreet message to the author about the sudden death of Albino Luciani in his papal bedroom on the night of September 28, 1978. The newly elected Pontiff was on the cusp of making sweeping and revolutionary changes in the Vatican when he died under mysterious circumstances.

Albino Luciani, Yallop writes in the prologue, had been pope for thirty-three days on September 28th, 1978. “In little more than a month he had initiated various courses of action which, if completed, would have a direct and dynamic effect upon us all. The majority in this world would applaud his decisions, a minority would be appalled. The man who had quickly been labelled “The Smiling Pope’ intended to remove the smiles from a number of faces on the following day.”

It never got to be. On the morning of September 29, 1978, Sister Vicenza Magherita entered the papal bedroom to look up John Paul 1 as she was wont to. It was routine for John Paul, an early riser all through much of his adult life, to sip the coffee Vicenza had left in an adjoining room in the Papal quarters. She had been part of the domestic staff of Luciani’s bishopric period in Venice for more than two decades.

But on that morning, and very unlike him, the Smiling Pope was yet to come out for his traditional coffee. By the time Vincenza entered the pope’s bedroom, there was certainly no smile on John Paul’s face. His skin was cold and the fingernails were unusually dark. No pulse. The Pope was dead!

From then on, senior officials of the Holy See, starting with Secretary of State Cardinal Jean Villot, began a series of cover ups to misinform the public about the real cause of Albino Luciani’s unexpected demise. Not only that, Yallop insists, the reforms the Smiling Pope hoped to begin were aborted. Even the planned re-designation of cardinals and prelates who were members of the Masonic Lodge, contrary to their oath of office, never got to be, as well.

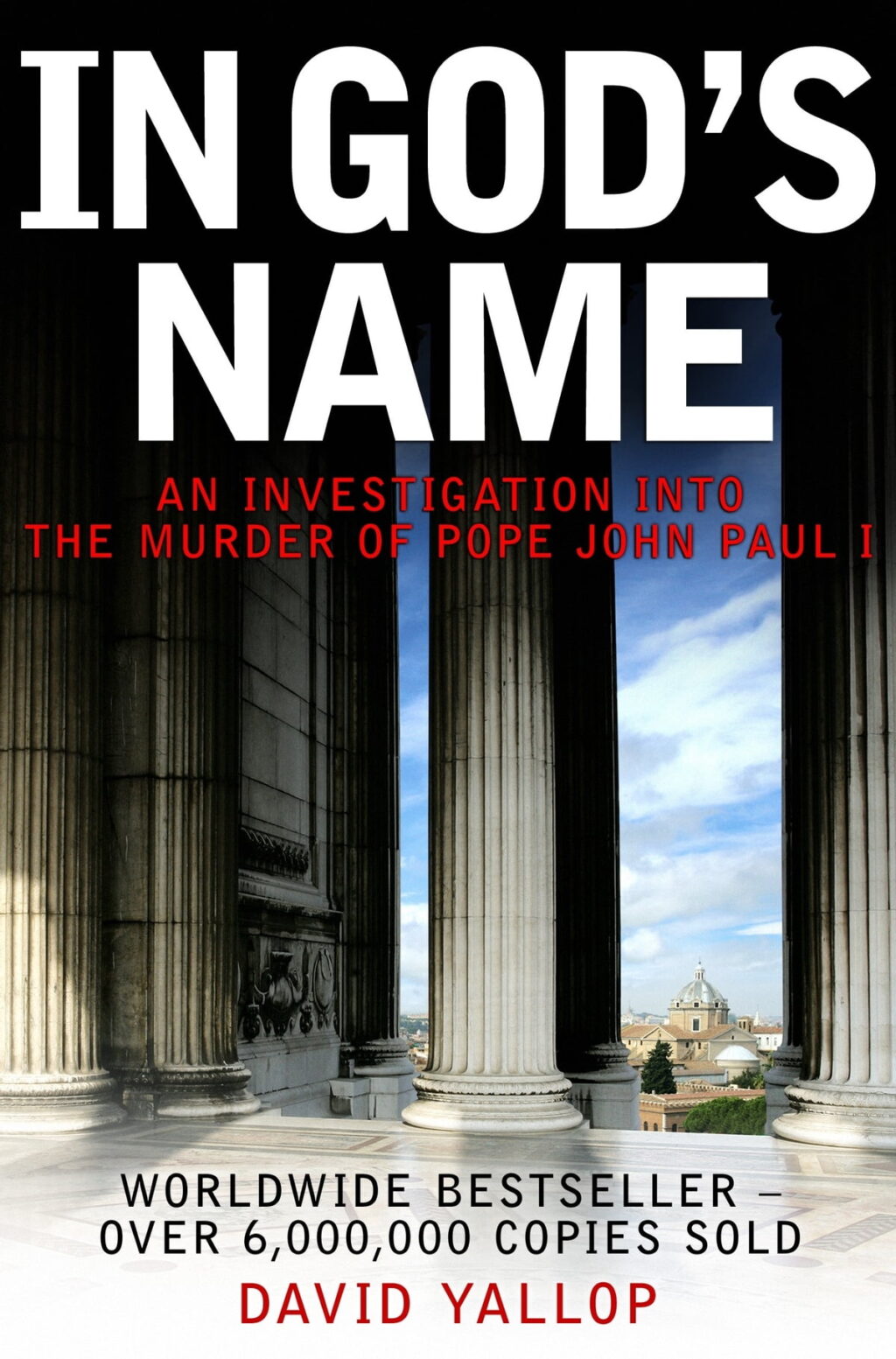

In God’s Name received rave reviews soon after it was published by Jonathan Cape in 1984, urging the Vatican to respond to some of the charges by Yallop. They never did, only dismissing it as “infamous rubbish,” then accusing the author of “taking fantastic speculation to new levels of absurdity.”

A big-foot British investigative journalist himself, Yallop presents his case persuasively against the Vatican: the murder of a pope on a revolutionary mission to cleanse the temple of God of the financial improprieties it was enmeshed in; the cover up of the death of the said pope after only 33 days as Pontiff and the subsequent gang-like murder of other individuals ranging from judges and investigators to journalists and some of the principal actors like Michele Sindona and Roberto Calvi.

This reviewer first read In God’s Name in 1990 as a just-about graduating student from the Ekenwan Campus of University of Benin. It was the 1984 edition. A month or so ago, a friend, Paul Idoro, brought this 2007 revised edition to work. Seeing it elicited that nostalgic feeling readers often experience after reading a book for the first time and coming across it again. I asked to borrow and read it again – thus this review.

The latest publication is longer 343 pages, with more details and a postscript by the author on developments so far. But the central question remains: how and why did the new pope, fit as a fiddle, die suddenly after only 33 days in office? Why did the Vatican embark on a cover up exercise soon after the death of Pope John Paul 1? How come an institution pledged to servicing the poor, is now in cahoots with big businesses of dubious provenance to the extent of taking over bankrupt companies or even bankrupting some?

Albino Luciani was an unusual candidate for the Papacy. Following his predecessor, Paul V1’s demise in August 1978, the cardinal from Venice was not a favourite among his red-capped colleagues to replace Paul V1. While some of his co-cardinals lobbied hard to be elected during the conclave, Luciani was somewhat aloof from it all, preferring his bishopric duties in his native Venice. If he ever got elected, he told some close friends and a few fellow cardinals, he would turn it down. He did not.

With 99 votes to Cardinal Siri’s 11 at the fourth ballot, Luciani won with a very wide margin. “Do you accept your canonical election as supreme Pontiff?” Villot asked him. He hesitated but then urged on by Cardinal Lorscheider of Brazil, answered: “May God forgive you for what you have done in my regard. I accept.”

Unlike The Dark Side of Camelot which critics dismissed as muck-raking, In God’s Name received rave reviews from newspapers and magazines across America and Europe and from Down Under. “Deeply disturbing,” Aberdeen Evening Express thundered at the time. “If only a small percentage of it is true then the Vatican and the world have much to fear, for God appears far from home.”

The Economist had more to say about Yallop’s meticulous research: “His book has two strengths,” the reviewer began. “It brings up to date and tells well the story of how the Vatican has conducted its financial affairs. The portrayal of the hitherto little-known John Paul 1 is also excellently done…an engrossing and disturbing book. It reflects no credit on the Vatican that its spokesmen affect to view the charges with contempt and ignore the questions raised.”

Yallop takes readers through the result of years of investigative work, giving them an insider’s account of the central character’s journey to Rome thus evoking another journey made by another Paul centuries before, the death of Pope Paul V1 and the empty throne. The British journalist couldn’t have been present at the Conclave during the search for a new pope, his reconstruction of the transactions at the time – the meetings between and among the cardinals, the hopes and aspirations of the early candidates, all of these the author limns very well for readers. Nor can you fault his painstaking research and report of the fraudulent financial dealings the Vatican got involved in through the very man at then head of the Vatican Bank, Archbishop Paul Mackincus aka God’s Banker.

Yallop not only avail readers with minutiae of the mind-blowing transactions by Vatican proxies with bent companies, we get to know of the habits of the principal players: Calvi with a severe colonel moustache who encouraged anyone who wanted to be somebody to read The Godfather. He always had a copy wherever he was; Licio Gelli, the master puppeteer and head of P2 who had a handful of presidents and prime ministers kneel before him even though he held no known designation in any government office; Umberto Ortolanni the point man between the Vatican and the various shady business men that worked for the Holy See.

In God’s Name reads like a thriller, an action-packed thriller with the customary assassinations and suicides: As head of Bank Ambrosiano in Italy, Calvi was neck deep in many of the takeovers of the bankrupt companies and many more he bankrupted. No surprise he was suicided, according to the author, from Blackfriars Bridge in London. Before then, his secretary jumped out of the office window. Three or more journalists and magistrates were also taken out, sometimes days after testifying against accused persons like Michele Sindona, himself a Sicilian who applied the Sicilian solution when necessary.

Of course, Sindona got his comeuppance while serving a jail term in the U.S. He shouted one morning after sipping a cup of coffee: “The have poisoned me.” He was dead two days later.

Such sponsored assassinations lend credence to Yallop’s contention that Pope John Paul 1 was murdered because of the revolutionary measures he hoped to effect as Pontiff. As any detective will tell you, there are usually other murders after the first one. But was the “Smiling Pope” actually killed as Yallop would have us believe?

Even now, it is still subject to speculation, with conspiracy theorists having a field day on the matter. But some medical experts insist Albino Luciani had medical issues before he became pope. Witness, for instance, his swollen ankles, his harsh cough that seems to make his body jump and chest pains.

Forty-four years after the death of Albino Luciani and 38 years after the first edition of In God’s Name, no one is any nearer the truth on that late night or early morning of September 28, 1978, partly because of the confounding role played by the mafia and high-ranking members of the Vatican at the time of death. Any of these men – Marcinkus, Cardinal Jean Villot, Roberto Calvi, Umberto Ortolani and Michele Sindona would have benefited immensely from the premature demise of John Paul 1.

The first three were residents of the Vatican at the time and highly regarded Christian leaders as well. So, was Albino Luciani betrayed by any of these brothers in Christ? “I admire Christ,” Mohandas K Ghandi once said, “but not Christians.”

More Stories

Vaping in Nigeria: Green outside, deadly within

Atrocities against the Nigerian Police: When the protectors are abandoned

When greed walks free and duty goes unpaid — The case for police pension justice