… Continued from last edition…

2. Altered presentation of diseases.

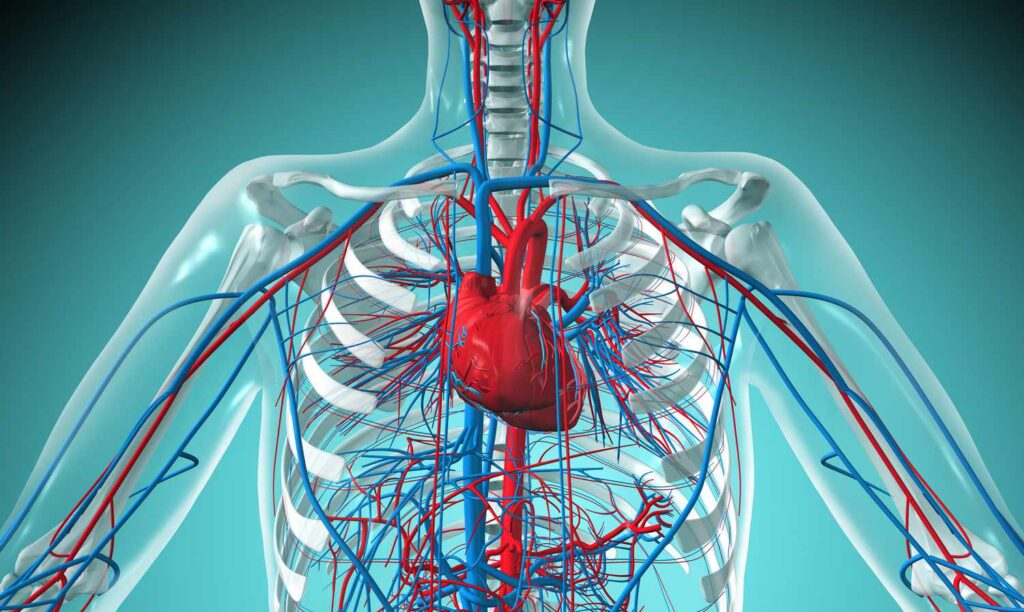

While chest pain remains the most common and important symptom of Coronary artery disease (CAD), dyspnea in the absence of chest pain is a commonly reported symptom, particularly in older adults, women, and those with multiple comorbidities. CAD symptoms may also include nonspecific problems, including fatigue, weakness, and decline in physical activity or function, so it is important to maintain a high-index of suspicion in those at risk. The concept of altered presentation of disease among older adults applies to a number of conditions, including CAD. A lack of understanding of this phenomenon can lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment, and result in worse outcomes for older adults. While chest pain remains a common and important symptom of heart disease, dyspnea in the absence of chest pain is even more commonly reported in older adults. In the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) registry, dyspnea was the primary presenting complaint of CAD in nearly 50 percent of the participant’s ages greater than 85 years. Any medical illness may present nonspecifically and be multifactorial among older adults, particularly those in frail health. Nonspecific symptoms related to an underlying medical illness include changes in cognition, difficulty with balance and falls, new urinary incontinence, or a general change in functional ability. Older adults may also be less likely to report significant symptoms due to pre-existing conditions, cognitive impairment, or a desire to minimize symptoms. Likewise, health care providers may minimize complaints among older adults with complex medical illness or frail health.

3. Multimorbidity

Cellular senescence, inflammation, oxidative stress, telomere attrition, telomerase activity, and apoptosis are biological factors underlying aging and the development and progression of CVD and can also provoke the development of other disease states over time. The accumulation of chronic conditions as a result of genetics, lifestyle choices, environmental factors, treatment of prior conditions (e.g., CVA as a complication of coronary artery bypass grafting) and aging itself culminates in a vastly heterogenic older population of adults with multiple medical problems. The prevalence of multimorbidity (the coexistence of 2 or more chronic conditions) rapidly increases with age such that it occurs in over 70 percent of 75 or older. In older adults with heart failure the burden of multimorbidity is significant with over 50 percent having 5 or more coexisting chronic conditions. Clustering of multimorbidity occurs both at a CVD level, where heart failure frequently exists with ischemic heart disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation and at the non-CVD level where heart failure is commonly associated with diabetes mellitus, arthritis, depression and frailty. The impact of multimorbidity is particularly evident in the management of heart failure where increasing non-cardiac comorbid conditions is associated with an increase in re-hospitalization and mortality. In addition, the societal cost of multimorbidity is substantial with increasing costs per number of chronic conditions such that individuals with 6 or more chronic conditions on average have over three times the spending compared to average per capita Medicare spending.

4. Geriatric syndromes

Geriatric syndromes represent clinical conditions common in older adults that share underlying causative factors and involve multiple organ systems. Unlike traditional medical syndromes, they do not fit a discrete metabolic, pathological or genetic disease category.Examples of geriatric syndromes include incontinence, cognitive impairment, delirium, falls, pressure ulcers, pain, weight loss, anorexia, functional decline, depression, and multi-morbidity.

4.1. Delirium

Delirium affects over two million hospitalized persons each year and is estimated to affect between 25 percent and 60 percent hospitalized older adults. The hallmark of delirium is characterized by its acuity, fluctuating course, alteration in global cognitive function and reversibility. In addition, a common feature relates to an altered level of consciousness resulting in both the familiar hyperactive and agitated form and more frequently (over 60 percent of cases) a more hypoactive and under-recognized phenotype. Dementia and mild cognitive impairment, in contrast to delirium, feature a more chronic progressive course and may affect a more specific cognitive domain pattern. While patients with dementia are more at risk of developing delirium, it is frequently under- recognized and not adequately managed within that population. Delirium is associated with prolonged hospital stay, increased costs, increased readmission rate to the hospital (12 percent – 65 percent at 6 months), and higher in-hospital and 1-year mortality. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) offers a validated screening tool to diagnose delirium. Per the CAM, delirium is likely present if the patient has both an acute onset with fluctuating course, inattention, and either disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness. Key risk factors for delirium include older age, cognitive impairment, surgery, polypharmacy (especially medications with anticholinergic properties), infection, sensory impairment, psychoactive drugs, comorbid illness, and functional decline. Precipitating factors during an acute illness include hypoxia, electrolyte abnormalities, dehydration, malnutrition, medications, and alcohol withdrawal. Environmental factors also contribute to problems, including tethers such as catheters and IVs that contribute to risk of falls, noisy wards, and frequent tests and procedures that further disrupt diurnal rhythms and sleep. Key points: Delirium is a common complication of hospitalization and surgery among older adults. Assessing risk for delirium and implementing a multimodal intervention can prevent its onset. Identification of other potential hazards of hospitalization for older adults, including sleep disruption, dehydration, malnutrition, and immobility, can improve outcomes.

4.2. Dementia

Dementia is prevalent in approximately 13 percent of community dwelling older adults over the age of 65 and increases to approximately 40 percent by the age of 80. In adults over the age of 65 with a diagnosis of advanced heart failure these estimates can reach 30 percent – 60 percent. These figures likely underestimate the prevalence due to reduced patient and provider recognition of the disease, particularly in the early stages. The most common causes of dementia globally are Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia which can also co-exist and result in a more progressive trajectory. The presence of dementia significantly increases the financial cost, management complexity and mortality rates for an older adult. In older adults who are classified as frail the prevalence of cognitive impairment is five times greater than those who are not frail. Moreover, the combination of these factors causes a more rapid decline in cognition and disability. Hypertension and frailty also lead to a combined effect, with increased risks for the development of mild cognitive impairment, a prodromal phase of Alzheimer’s type dementia. For an individual that has both HTN and mild cognitive impairment, institutionalization and mortality rates are similar to those with dementia and significantly higher than those with HTN alone. Executive function, specifically, appears to be impaired in older adults with CVD and can dramatically reduce their capabilities to initiate and participate in their disease management. High rates of unidentified cognitive impairment in older adults suggest that periodic screening is necessary to accurately establish future risk and determine benefits of simplification of treatment strategies.

4.3. Frailty

Frailty encompasses a biological decline across multiple interrelated organ systems and a subsequent loss of reserve in response to stressors, such as acute illness, and can result in a poor tolerance CVD and/or to CVD therapy. Frailty is an independent predictor of a wide range of CVD including subclinical CVD, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure and CVD mortality. Objective frailty, in the most part, refers to a phenotype that includes weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness, and low levels of activity. In addition, cognitive impairment now appears to be a common and significant component of frailty and should be assessed for in combination with objective tools. Currently, there is no widespread standard for assessment of frailty in the CV setting despite the recognition as a significant factor in the evaluation of an older adult with CVD. Many parameters can be used to assess frailty. Despite the recognition of frailty as a significant factor in the evaluation of an older adult with CVD, there is no widespread standardized tool utilized for the assessment of frailty although numerous methods have been used. Grip strength and gait speed are sensitive and frequently used physical functional measures, but faltering cognition, ADLs, and other deficits are also sometimes used to define frailty.

4.4. Sensory impairments (hearing and vision loss)

Hearing and vision loss are very common in the geriatric population, with more than 40 percent reporting difficulties with hearing, and more than 13 percent having visual impairment after the age of 65 years. Age-related hearing loss or presbycusis, the most common type of hearing loss in older adults, is a multifactorial high frequency sensorineural hearing loss that commonly results in a component of impaired speech discrimination. Cerumen impaction and chronic otitis media leading to conductive hearing loss may be present in up to 30 percent of elderly patients with hearing loss, and can be treated by the primary care clinician. Patients, clinicians, and health care staff often do not recognize hearing loss, particularly in its early stages. Older adults may not volunteer difficulties associated with the hearing loss through a fear of social embarrassment. Implications include increased susceptibility to delirium, poor health literacy, and misdiagnosis of depression and/or dementia.

More Stories

Kemi Badenoch recommends disabled toilets for transgender people

‘I prefer dating older men,’ says Nollywood star Beverly Osu

Access Bank reacts to viral report of staff who filmed colleagues in restrooms