Afrobeats to the world has hit a new conundrum. The entire movement has achieved saturation and needs to rethink how it has approached this market. There is enough capital to fund three small countries and an Island nation, but not enough local stars exist to deploy this capital. And so the labels are stuck.

The distribution houses are at an impasse with culture. They are sitting on money that needs to get working. The labels have thrown cash and contracts to every singer and producer who has a bit of leverage — sometimes that leverage can be just one hit song — and inundated the market with artists who flatter to deceive.

How did they get here? By their hands, of course.

Afrobeats to the world has never been about building the local industry and empowering the market to take off independently. While the theory that gets bandied around the Lagos music professional circuit supports this claim, the practicals, so far, hug another path.

The complete premise of foreign music companies arriving on West African shores with boots on the ground, centres on extraction. These companies are mining the art from Nigeria and shooting it into foreign markets, with the hope of the music taking off in the West. The entire operation has been a play to mine the game for the best of itself, create a conduit to package and distribute it elsewhere, while telling the world that Nigeria is taking off.

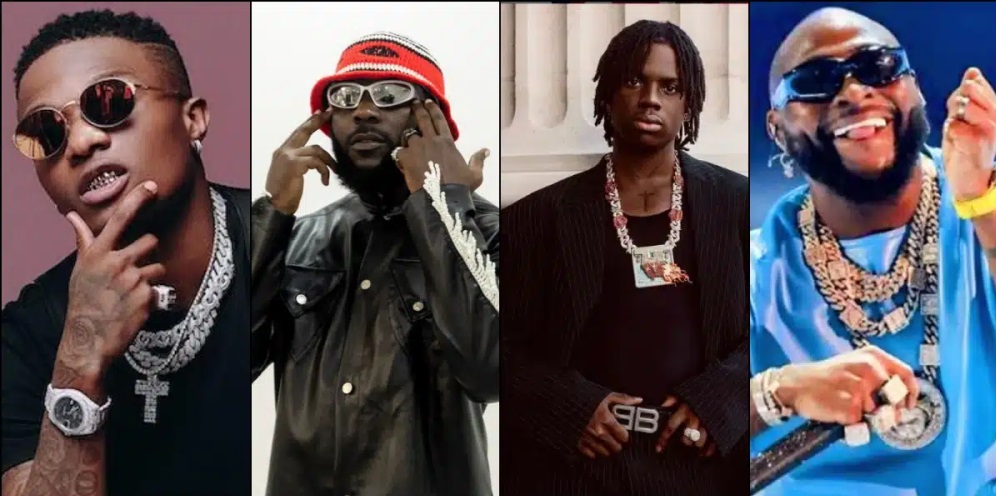

Wizkid, Davido and Burna Boy were the guinea pigs of this expedition. Since 2016, they have had to define the rules of engagement, initially leading the market with failed attempts to fly internationally, before finding a path to generating value from home and abroad. Think of 2017’s “Sounds From the Other Side,” and how it fell into a black hole. And then there was 2016’s “Son of Mercy” which had Davido flailing in the wind, without an anchor to his homegrown fan base.

Early problems aside, Afrobeats to the world have rallied by re-educating both at home and abroad. Local stars create art with a global outlook, while foreign consumers alter their consumption habits to accommodate and highlight this new sound of Africa offering novel escapism. The resultant success made the labels rapacious, signing every creator who offered a smidgen of connectivity. “Market share! Market share!” they chant all around the city, sharing deals across every leveraged artist. Everybody you know in music who has a hit song or has done anything of note has a foreign label accounting for where they make money, how they make that money and where they channel their creativity.

But there is an unforeseen problem biting at the heels of the local music industry; We don’t mint enough stars to guarantee enough business for the foreign labels. Nigeria, for all its continental domination, has an average of two breakout stars a year. 2023 gave us Odumodublvck and Shallipopi. Two artists submerged in questions about their place in the game. But they already have their deals in place.

Odumodublvck is signed to Native Records, a company owned by Seni Saraki and Teezee, who are in bed with Def Jam Recordings. Def Jam also has the singe-producer, Bloody Civilian, the best-kept secret of Afrobeats. Shallipopi is signed to DVPPER MUSIC, a local distribution company in bed with Virgin Music Nigeria. By extension, his deal is in the bag. Afrobeats to the world already claimed our latest offering. These companies are that effective. And so, the current market saturation comes with a need to engineer a new way to generate value.

Music companies are now faced with the rudimentary work they have avoided for so long; building from the ground up. Instead of latching on to a great story and steering the narrative in their direction, they are now faced with servicing the entire value chain by creating new stars from inception.

So far, everyone has won by avoiding kindling artistic fires. They all sat back and watched local teams fan the lame. And when the flares began, they swooped in with the fuel to make it bigger, licensing deals, project deals, single deals, and every other deal that doesn’t have the word “development” in it. But that has to change. The market demands it. With the lack of new stars to amplify, the majors now have to seek a new path. Find the kindling and strike stones until smoke erupts. Bottom-feeding, but with finesse.

Enter artist development. The major task for all the music executives in 2024 is talent scouting, building from the ground up. That means unearthing the best creators from the farthest reaches of Nigeria and throwing them a deal that allows them to actualise their potential. It is planting season now, and everyone has to till the earth. The broader implication of this means, that Afrobeats to the world and the search for future gold now has to leave the artistic hubs of Lagos and Abuja, into fringe creative centres existing in Uyo, Calabar, Enugu, Abeokuta, Port Harcourt and Kaduna. This is the real work. The one task that defines this era of creative enterprise in the Nigerian music industry.

This is great for the local music industry. Think of this as the money going around and hitting the grassroots of the current Nigerian creative class. Think of this as the first real benefit of Afrobeats to the world in the wider ecosystem of creativity. One in which Sade in Ibadan and Ubong in Uyo will now possess access to the greatest music companies in the world and their refined, standardized systems.

Early runners have found a hack and they are outsourcing this work. Think of United Masters, the US-based major distributor for indie artists, choosing to partner with Sarz and The Sarz Academy to develop new talents. EMPIRE, the current market-share leader already has the Pepsi Music Academy in full flow. Many more are straight up going the way of locking in mushroom agencies to handle the scouting for them.

2023 gave Afrobeats to the world its most stark realization. We don’t mint enough stars for the capital we attract. We either solve for that or plateau. And you know what happens when a culture hits the stationary phase. To stand still is to fall behind.

More Stories

Why I dated young men – Shaffy Bello

Top boy actor Micheal ward faces multiple sexual offence charges

Priscilla Ojo, Juma Jux announce pregnancy